Please Don't Use JSON Web Tokens for Browser Sessions

January 28, 2024

JSON Web Tokens

In the JavaScript community, JSON Web Tokens (JWTs) generally stored in localStorage have become a popular way to implement user authentication, especially for Single-Page Apps (SPAs). That's the way I first learned when I picked up Express in 2016. In the 2010s when I learned Django I used Jinja templates and session cookies and SQL, and in the mid 2010s the new hotness was React Express Mongo and JWTs. Every resource on node/Express authentication recommended doing authentication this way, so I didn't question it for a long time.

On StackOverflow and across the web dev tutorial-o-sphere, session cookies are often portrayed as outdated, a 2000s internet technology. If you search around for tutorials about "how to implement authentication in NodeJS", many posts imply that we all ditched old-fashioned session cookies when we moved from "traditional" web apps based on Rails, Django, etc to the new school of Vue, Angular, React, and the rest. Numerous blogs claim that JWTs are "more secure", then proceed to describe an inherently insecure way to use them!

This is a mistake. JWTs are fantastic for their intended purpose: "representing claims to be transferred between two parties." That's why we use them in OpenID Connect (OIDC) to delegate authentication.

This isn't an anti-JWT article. If you want to present proof of claims between parties, as we do with OAuth and OpenID Connect, then a JWT is the right way to go (though keep an eye on PASETO...). My point is that, despite what a lot of the internet tells you, JWTs are not appropriate for browser sessions. I've tried to make this post accessible to newer developers, but there are plently of links to additional resources if you want to dive deeper.

My TL;DR: depending on how you implement it, using JWTs for browser sessions is either...

- inherently insecure (if you store reusable JWTs in

localStorageor anywhere else accessible to JS) - or is just "session cookies with extra steps" and no advantages if you put your JWT in an

HttpOnlycookie.

A common dangerous pattern: JWTs in Local Storage

Before getting into it, I want to be clear: JWTs and cookies are orthogonal concepts. You can put JWTs in cookies, you can have cookies that have nothing to do with JWTs, you can send JWTs in non-cookie headers or by other means if you have a reason to. JWTs aren't an alternative to cookies.

The articles I'm criticizing in this post talk about "JWTs versus cookies" because those articles are instructing developers to use JWTs, generally stored in localStorage and sent in the Authorization header, instead of session cookies.

"Do not store session identifiers in local storage as the data is always accessible by JavaScript. Cookies can mitigate this risk using the httpOnly flag." -OWASP

The browser is not a trusted client. The browser is a dangerous landscape of end-user-installed browser plugins, and a lot of third-party JS scripts we invited in for analytics, ads, support chat, and so on, often at the behest of marketing/support teams. And on top of that, we have all the npm dependencies of our front-end JS code itself.

If we put an authentication token in localStorage, XSS through flawed dependencies or other avenues could mean that every active session in our app gets exfiltrated quite trivially, and we are liable. It is a poor decision to store sensitive data like credentials anywhere accessible to JavaScript in the browser.

Could we do some sort of refresh token rotation scheme in the browser to get around this? We could make the refresh token act as a one-time token. We could even invalidate the whole token chain if any refresh token is used a second time. That would incur significant costs of statefulness and complexity, but would it at least allow us to have JWTs that are accessible to JavaScript in a secure way, so they cannot be exfiltrated by XSS?

Nope. A smart XSS attacker can wait until the user is done using the app, take the last refresh token issued, and use it as if they were the legitimate user. Once the real user comes back to the app, their reuse of the refresh token they were last issued will trigger the chain to be invalidated at that point, cutting the XSS attacker out of the loop. But the XSS attacker had access during that whole period of user inactivity, and can repeat the process to obtain a new refresh token when the user becomes inactive again. (See Dr. Philippe De Ryck's excellent webinar on the subject: "The impact of XSS on OAuth 2.0 in SPAs")

Another approach to thwart XSS is to attempt to hide the token. Auth0 recommends storing tokens in browser memory* using Web Workers, and Auth0's SPA SDK takes this approach by default. There are two problems with this:

- Storing the token in-memory means it is gone when the user closes the tab or navigates away from your website, so if this is the way you're doing sessions, your users will have to log in every time they open your website. Unless you're making a banking application, forcing users to log in so often is generally an unacceptable user experience. (To make logins persist, developers commonly store the token in

localStorage, as Auth0 suggests* for persistence, noting the XSS vulnerability.) - Even though it's hidden in a sandboxed Web Worker context, an XSS attack can still inject code into the sites where the main context interacts with the Web Worker, and ultimately obtain the JWT. This article by Dr. De Ryck demonstrates such an attack.

* Please note that the Auth0 suggestions I'm citing about token storage are concerning OAuth 2.0 tokens, and not JWTs for sessions between a SPA and its backend HTTP API. Auth0 states that your SPA should only use OAuth 2.0 tokens if it calls multiple APIs that reside in a different domain. I'm just bringing up Auth0's suggestions to try and build a steel-man case of how to best secure our session JWTs. See "What Auth0 actually recommends for SPAs" below.

Hiding the token in a JS closure has similar weaknesses.

Ultimately, you cannot hide anything that is accessible to your JS from malicious XSS JS. If you get XSS, and have your authentication token in localStorage or in memory (or in a non-HttpOnly cookie), it's game over.

Some readers might think "but I'm already screwed if I have XSS! Who cares if the XSS has direct access to my authentication data or not?". That's true, XSS is very bad. After following all best practices to prevent XSS, I'd argue you should still take the limited means available to you to mitigate what power XSS has in your application. With an HttpOnly cookie, a successful XSS attacker can still make requests impersonating the user, relying on the browser to send the cookie in requests to your backend server. The difference with an HttpOnly session cookie versus a JWT in localStorage is that with the cookie, the attacker can't exfiltrate the credentials because the browser won't send the cookie elsewhere. It's not a huge win, but it is still a win.

(And okay, okay, they can exfiltrate it with XSS if they control a subdomain and if the cookie has Domain set to the apex domain... but credentials in localStorage can be exfiltrated with XSS no matter what.)

You could submit the JWT in an HttpOnly cookie, which might seem to be the best of both worlds... until you come up against invalidation.

"Stateless" JWTs for sessions: The Problem of Invalidation

Software land is bedecked with dreams of stateless, even serverless applications. Part of why JWTs are supposed to be so cool is because they enable a user authentication without stateful sessions. A stateless JWT contains session data coded directly into the token. The name is maybe confusing if you're looking at it from the JWT's point of view, because a stateless JWT does hold state. But it's named this way because putting state in the stateless JWT enables the server to be stateless with regards to sessions.

Using a JWT to authenticate sessions seems at first like a great solution. A user makes a request to an endpoint of our HTTP server with the header Authorization: Bearer <jwt-here>. We merely have to verify the JWT's integrity, and then we can trust all the claims of the token. We can then achieve a broad set of functionality without ever having to hit the database to get any data supplied by the token. This is performant, and pleasingly stateless.

However, because we've avoided stateful sessions, we have run into the problem of stale JWTs. What if someone left their session open on a public computer, or had their device stolen, and wants to log out all their sessions? Or, what if we want to revoke a user's permissions after they leave an organization?

We need a way to invalidate these stateless JWTs. The only way to do this is through blocklisting JWTs (or some variation of that). This means each time our server looks at the stateless JWT, it has to access our stateful JWT blocklist/allowlist/etc to make sure our application hasn't invalidated the token. The statelessness is gone. So we might as well have used stateful sessions!

Blocklists aren't the only way to do invalidation. JWTs have expiration built in (the exp claim). So we could make the tokens expire quickly, let's say every 5 minutes, and just keep re-issuing them. We don't want users to have to re-login every 5 minutes, so we can issue a user one long-lived refresh token that we use to fetch a new short-lived access token. The short-lived token has all the user-associated data which we don't want to get stale, including authentication data, possibly authorization data allowedResources: ["someOrganizationA"] and maybe even user metadata. Instead of needing to hit the database every time our user hits an authenticated route, we only need to do it when they refresh their short-lived token. But you still have stateful sessions, they're just more database-light. And this approach means accepting a 5 minute staleness, so the admin that just got demoted has that much time to do whatever schenanigans an irate ex-admin does with a stale JWT.

If you want invalidation (which for sessions, you really do!), then you need a stateful blocklist/allowlist, which is as much overhead as a database of session tokens.

The "stateless" promise doesn't hold up. All this is a lot of work to do something that session cookies do more simply and more securely.

Bearer Token: Misappropriation from OAuth 2.0

The convention of using the header Authorization: Bearer <token> comes from an OAuth 2.0 specification. It's meant to access OAuth 2.0 protected resources.

OAuth 2.0 is not meant for sessions between your one frontend browser application to your app's backend HTTP server. It is a framework to allow an application to obtain limited access to another application on behalf of a "resource owner", often a human user.

In the olden times before OAuth, if I wanted to allow a social media app to access my email contacts, I had to give the social media app my username and password to my email for it to log in as me and check my contexts. Obviously this is a security nightmare! The social media app has my full email login credentials (which I can only hope it's storing securely). It has the ability to read all my emails, send emails, even lock me out of my account by changing my password!! That's a huge risk to me the user, and a huge liability for the social media company.

We needed a way to grant limited access to applications, and thus OAuth 1.0 and eventually 2.0 were born. OAuth allows applications to delegate limited access, so some app can read my contacts or do other limited actions in a way that is transparent to the user and revokable. (PS: this short article about OAuth's history is a nice quick summary.)

But somehow, SPA developers began taking pieces from OAuth out of context and using them for the long-term authentication of browser sessions where there is no third party involved. There are many tutorials out there that suggest using Authorization: Bearer <jwt-here> where a website in a browser is directly authenticating to its backend HTTP server without any OAuth concerns present at all. It doesn't make sense to do use Authorization: Bearer <token> to do that.

HTTP Trivia Corner!

The earliest HTTP, retrospectively called 0.9, did not have headers. Authorization: basic-credentials | ( auth-scheme #auth-param ) is one of the original headers from HTTP 1.0, where HTTP headers were first introduced.

🌈🌟 NOW YOU KNOW! 🌈🌟

Speculations: Where did this JWT-for-sessions trend come from?

Stepping away from Auth0, why do so many tutorials out there suggest using JWTs for sessions, particularly with Authorization: Bearer <token> and storing the JWT in localStorage?

My armchair theory is that new JS developers get taught to use providers like Auth0 for authentication, in bootcamps or in "how to make an express spa app" tutorials. Their initial training is usually frontend-heavy, and based on using a handful of external third-party APIs perhaps without any backend of their own. Using a third-party auth provider as your first experience implementing authentication kind of misrepresents auth as requiring OIDC and the delegation that entails. Then these developers sloppily borrow concepts from Auth0/OAuth/OIDC to implement their own auth, thinking cookies are outdated and JWTs are the new cool better technology to use after having read a lot of pro-JWT marketing material? I'm not sure.

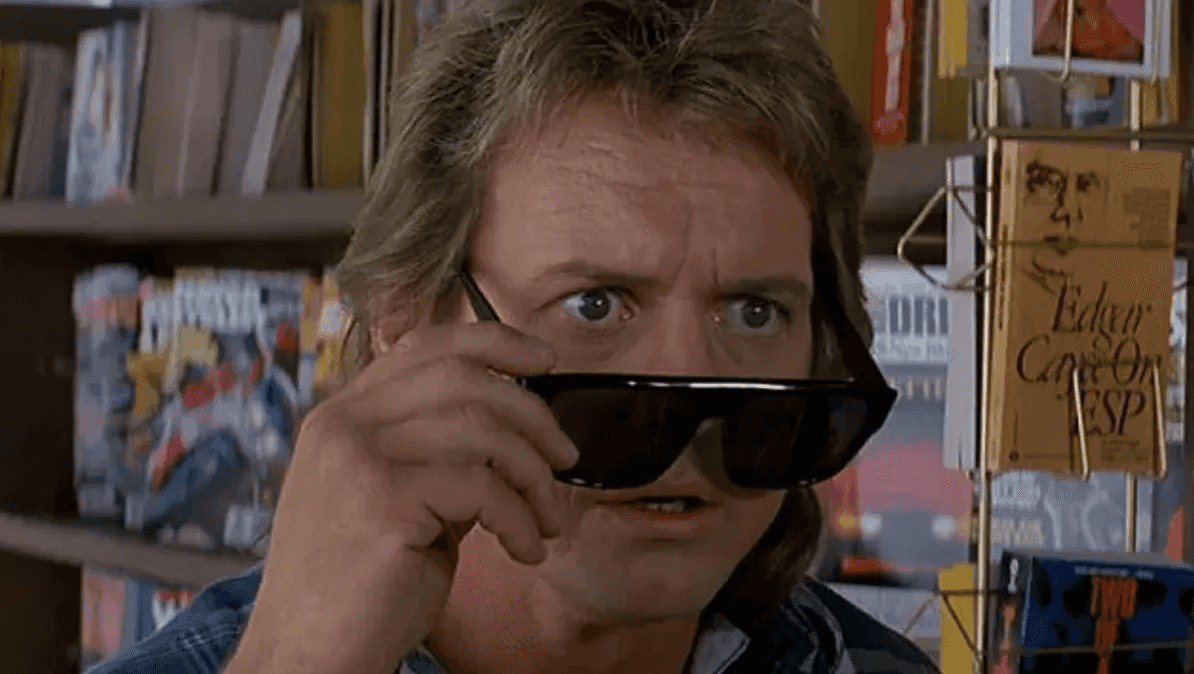

Randall Degges, "Chief Hacker" at Okta and former dev advocate at Stormpath, gave the presentation "JSON Web Tokens Suck" at ForwardJS (slides). If you're reading this far into my post, you would probably get something out of watching it.

Randall blames himself for the popularity of JWTs, and more specifically Stormpath, Okta, and Auth0:

The security industry is super f***ing boring and slow. Nothing exciting ever happens, like ever. When JSON Web Tokens came around, someone wrote a blog post about the possibility of using them to store session information, it got a bunch of buzz in the security space, and Auth0 and Stormpath started playing around with it.

[...]

We made a lot of money off of promoting JSON Web Tokens. And so at the end of the day, the reason why JSON Web Tokens are so popular today is because over the last 3 years [2015-2018ish] both of our companies strategically used them as a way to market to developers, not based around any sort of like legitimate security concerns, but purely because it's a valuable marketing ploy in the security industry where this stuff is not happening very often.

He suggests you validate these claims (JWT pun not intended) by searching google in an incognito tab for JSON web tokens and then noting how many of the top results are marketing pages for services like Auth0 and Stormpath. At the time of this writing Stormpath has been acquired by Okta and competitor Supertokens also has strong SEO here, but, yup. Note also that the most prominent JWT resource https://jwt.io/ is by Auth0/Okta!

I'm not trying to make the argument that Okta/Auth0/etc are insecure. Whether you use them securely or insecurely is up to you.

Rather, the problem I'm targeting here is that many developers use JWTs in places where they aren't appropriate because it's a self-perpetuating trend and session cookies are wrongly seen as old-fashioned, irrelevant, and insecure. Those companies seem inadvertently somewhat responsible for the trend, but whatever, what I hope you get out of this article is to not a negative impression of these companies, but rather an understanding of why it's a bad idea to use JWTs for your application's sessions in a pale imitation of these auth providers.

What Auth0 actually recommends for SPAs

When the SPA calls only an API that is served from a domain that can share cookies with the domain of the SPA, no tokens are needed. OAuth adds additional attack vectors without providing any additional value and should be avoided in favor of a traditional cookie-based approach. -Auth0 "Token Storage" docs (SPA tab), emphasis mine.

We can't really blame services like Auth0. They over-hyped JWTs, but the hype-happy JS community was eager to embrace a new cool thing, and was eager to misunderstand how the concerns of OAuth/OIDC/SSO are different than the concerns of session authentication for a website communicating with an API on a shared domain.

(However, it would be nice to see less docs quickstarts that say "don't store the JWT in localStorage, but as an example, we will.")

What's a Session Cookie?

A session cookie is a cookie with a cryptographically secure random string. OWASP recommends it's at least 16 bytes, with 64 bits of entropy. It needs to be implausible to guess, because that random string is the token that authenticates a session.

(Some session management libraries force this randomness by signing a given session token with a random string, in order to prevent newbie developers from using session tokens that are easily predictable incrementing integers.)

When a user authenticates to your server with credentials like their username and password, you check the credentials, then create a random session token and add it to your stateful sessions database so that that new session token is associated with that user. It might be something like a cookie with a value 39ur20fu2948fy34fy3fo983u20du83s, and a corresponding database entry like session_id: 39ur20fu2948fy34fy3fo983u20du83s, user_id: 123, session_expiration: 2024-01-29.

Now whenever you receive a request on an authenticated route, you use the session cookie's value to query the database where you're storing your session data, and if there's a matching non-expired session, you have authentication.

To invalidate a session, remove it from your database or otherwise mark it as invalid. This is the same as you'd need to implement JWT invalidation, but without all the extra steps and additional security hazards inherent to JWTs.

Cookie Attributes to Know

I already discussed HttpOnly (which prevents JavaScript from reading the cookie) and SameSite which provides limited protection against CSRF attacks. Another important cookie attribute is Secure, which restricts the cookie to only be submitted over HTTPS. Whether in a cookie or in an Authorization header, credentials sent over insecure HTTP can be read by anyone between you and the end server. If an eavesdropper can read your session cookie, or your session JWT for that matter, they can impersonate you for the duration of the session. Hopefully your server only accepts HTTPS, but the Secure attribute ensures the browser won't permit sending the cookie in an insecure HTTP context.

XSS versus CSRF

StackOverflow comments abound with "well actually, if you use a cookie for authentication, that's vulnerable to CSRF. You should just put a JWT in localStorage. If XSS happens you're screwed anyway."

This idea comes out of a misunderstanding of the risks. I explained above how a properly-configured HttpOnly cookie can prevent exfiltration of credentials in an XSS attack. If your credentials are accessible to JS, you can't prevent exfiltration in an XSS attack. That's a win for the session cookie in the XSS arena, but what about CSRF? In this section I'll talk about why CSRF is a solvable problem.

CSRF quick summary: CSRF takes advantage of authentication/session cookies to impersonate a user who is currently logged in to an application. Let's say there's a vulnerable ecommerce app, InsecureStore. Our victim is logged into InsecureStore via a session cookie. The attacker gets a victim to go to a malicious website, maybe by phishing or by putting a website on a typo domain or anything. On the malicious site, the victim is tricked into submitting a request to insecurestore.com, let's say by a hidden form that is triggered automatically by JavaScript on the malicious page. Meanwhile, insecurestore.com has an endpoint insecurestore.com/gift-card that takes a POST with application/x-www-form-urlencoded (or multipart/form-data or text/plain, these media types do not trigger a CORS preflight). The malicious page performs a POST to that endpoint to buy the attacker a gift card with the victim's money. Our fictitious insecurestore.com servers are checking the session cookie in order to authenticate requests, and because the victim's browser included their insecurestore.com cookies with that forged request, the servers process the request as if it's legitimate, and the attack is successful.

(PS: at the time of this writing, nothing exists on insecurestore.com. The story, all names, characters, and incidents portrayed in this example are fictitious. No identification with actual persons (living or deceased), places, buildings, and products is intended or should be inferred. 🙃)

Some newbie developers (I hope they're newbies...) in the comments sections of our vast Internet confidently state that the best way to protect against a CSRF attack is to just not use session cookies. As we've seen, the alternatives to session cookies are less secure. CSRF is something developers can control by implementing well-known mitigations. See OWASP's CSRF Prevention Cheat Sheet for details on how to prevent CSRF with the Synchronizer Token Pattern (stateful) or the Signed Double-Submit Cookie Pattern (stateless). Though you should use a tried-and-true library and not roll your own, it's still good to understand the mechanism.

Note also that an application/json endpoint isn't susceptible to the attack described above. Only requests using the three aforementioned media types: application/x-www-form-urlencoded, multipart/form-data, and text/plain may avoid triggering a CORS preflight (other conditions also need to be met). In a modern SPA, where you're making JSON requests to a RESTful HTTP server and never using traditional HTML form submission, a lot of the venues of CSRF are already closed off.

You should not rely on these inherent partial protections to mitigate CSRF, and should use one of the methods OWASP prescribes, but I think it's notable that CSRF is tricky to exploit for an HTTP backend that doesn't use HTML form media types. Here are some vulnerabilities that may allow CSRF even in a purely no-forms, all-JSON HTTP server:

- Maybe your server's framework will accept

text/plainor the other 2 "simple request" candidate media types, autoconverting them to JSON internally. Then the CSRF attack will go through without CORS stopping it. - Maybe you have an overly-permissive CORS policy: perhaps your

Access-Control-Allow-Originheader is dynamically updated to whatever the requester's Origin is, and yourAccess-Control-Allow-Credentialsis alwaystrue. So even anapplication/jsonrequest with theDELETEmethod could go through cross-origin, with the cookie included, because your CORS policy gave the victim's browser permission to do so. - Maybe none of these are true... until you update something on your server one day, and don't notice the change.

- Maybe the user has some plugin which opens up a security hole because of an overly permissive cross-origin policy within the plugin (like Flash), exposing CSRF vectors you don't expect.

(Examples from https://www.directdefense.com/csrf-in-the-age-of-json/)

The SameSite attribute on your session cookie (which is SameSite=Lax by default) will also partially protect you from CSRF, by preventing the browser from sending the cookie cross-site. However, there can be cases where Lax or even Strict won't protect you: if an attacker controls any of your subdomains, or if you have Lax and have stateful GET endpoints, or if you expose a client-side redirect that can be exploited. This PortSwigger article for more info about potential holes in SameSite.

So please do use CSRF mitigation along with your session cookies, even though a JSON HTTP backend makes it substantially trickier for a CSRF attack to be successful than it was for traditional HTML-form-based backends of the past.

Follow the OWASP guidelines, using a battle-tested library for Signed Double-Submit Cookies or Synchronizer Token, and your session cookie will be secure against CSRF.

What about stateless cookies?

Stateless cookies are implemented in a few ways: they might be cookies containing JWTs, or in some other format with no JWTs involved, usually with some library-specific signing and often encryption.

This turns out to be quite similar to Authorization: Bearer <jwt>, with the differences:

- PRO: Ability to use

HttpOnlyto make the credentials inaccessible to JavaScript. - CON: You need to be mindful of the 4kB max size limit of cookies.

Overall, we have the same invalidation and staleness problems with stateless cookies as we do with stateless JWTs sent in a header. "Stateless" sessions mean using a client-side token as a cache for session state. That opens us up to stale session state and takes away our ability to invalidate that session.

For example, in the stateless cookie library iron-session, the FAQ explains:

How to invalidate sessions?

Sessions cannot be instantly invalidated (or "disconnect this customer") as there is typically no state stored about sessions on the server by default. However, in most applications, the first step upon receiving an authenticated request is to validate the user and their permissions in the database. So, to easily disconnect customers (or invalidate sessions), you can add anisBlockedstate in the database and create a UI to block customers.Then, every time a request is received that involves reading or altering sensitive data, make sure to check this flag.

We have "stateless sessions," but our first step is to query the database to access server-side session state and verify that the "stateless" session's content is still current. It's stateful sessions with extra steps, and the addition of those extra steps is a security liability. If we ever skip the step to verify with the database, we'll have quietly created a hole in our authentication security.

Other JWT Security Concerns

This post is already very long and dense, but after describing perhaps too many details about CSRF defense for cookies, I don't want it to seem like the only security flaws of JWTs are vulnerability to exfiltration by XSS.

The fact that JWTs are only possible to invalidate through some stateful blocklist implementation is a scary thing. If your blocklist is permissive or slow to update, then compromised credentials cannot be revoked, and claims to authorization privileges in the JWT cannot be revoked. Your team will constantly be fighting temptation to allow holes in the blocklist: if it's too slow or unavailable, we don't want login to break for the "edge case" of invalidation, let's have it fail open! After all, we're validating the claims that our own servers signed, who cares if they're a little stale? We can give the appearance of logout by deleting the JWT on the client side.

If you are really motivated to use JWTs for sessions because you're struggling to scale your authentication infrastructure, the temptation to lean away from token invalidation will be even stronger.

The JWT spec is also rather permissive, and so JWT libraries must accept that permissivity. Any good introductory resource about JWT security will mention the "none" algorithm: an attacker can create a JWT with whatever claims they want: {user: popularCewebrityInfluencer, admin: true} and set the alg: none. If the backend developers made the common mistake of using whatever algorithm is specified in the JWT as the source of truth about how to verify it, the backend will see alg: none (which means "don't worry about it") and treat all claims in the token as valid. The attacker can literally write their own ticket.

You might think "well that's a rookie mistake, nobody serious ever ran into that." But, Auth0 themselves, the number-one JWT evangelists of all time, had an alg: nonE bypass in their Authentication API (the capital E is what cracked it). See the disclosure here. Again, I don't mean to pick on Auth0. IMO, this is a flaw in the JWT spec. It arguably shouldn't allow a none algorithm, must less require it as one of the two required algorithms!

Of the signature and MAC algorithms specified in JSON Web Algorithms [JWA], only HMAC SHA-256 ("HS256") and "none" MUST be implemented by conforming JWT implementations. It is RECOMMENDED that implementations also support RSASSA-PKCS1-v1_5 with the SHA-256 hash algorithm ("RS256") and ECDSA using the P-256 curve and the SHA-256 hash algorithm ("ES256"). Support for other algorithms and key sizes is OPTIONAL. -(JWT RFC 7519)[https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc7519#section-8], emphasis mine.

It seems like a weird choice.

There are also numerous security flaws that researchers have found in JWT libraries, owing to the inherent complexity of JWTs. Towards the end of this article from Securitum is a list of CVEs and GitHub issues from libraries.

JWTs are very complex, and offer many opportunities for security-botching mis-implementations and misconfigurations. Security is rarely simple and session cookies still allow developers to build insecure applications, but they're simpler than JWTs.

Thanks for reading!

This was a dense one! I hope you got something out of it. Please reach out if you have comments or corrections.

Further Reading

There are already a couple dozen links in this article, but here are some more!

Redis: JSON Web Tokens are Not Safe (e-book). Obviously Redis has a vested interest: "don't use JWTs, use session cookies instead, with the session tokens stored in Redis." But that is a robust and secure solution that I endorse, so I'm down to share their content marketing ebook.

The impact of XSS on OAuth 2.0 in SPAs - webinar by Dr. Philippe De Ryck. I'm not talking about actual OAuth in my post, but the same points this webinar raises are just as relevant to "using a JWT for session authentication in a pale imitation of OAuth" implementations.

Direct Defense: CSRF in the Age of JSON

Randall Degges: Please Stop Using Local Storage

Auth0: Critical vulnerabilities in JSON Web Token libraries lists vulnerabilities discovered in various JWT libraries. This post was originally written several years before Ben Knight found that Auth0 themselves were vulnerable to a alg: nonE signature exclusion attack.

joepie91's Ramblings - Stop using JWT for sessions and part 2 with a fun, "slightly sarcastic" flowchart